Thinking outside (and inside, and about) the box

The box-candle problem is an exercise that tests how we solve problems.

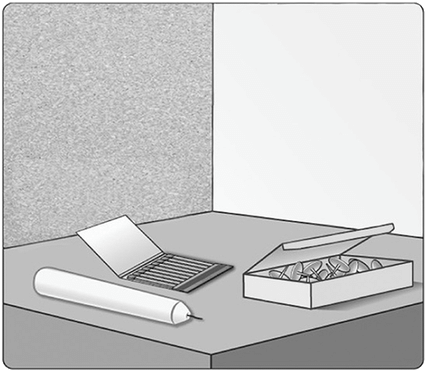

Individuals are asked to attach a candle to the wall so that it burns without dripping wax onto the table below. The materials provided are a candle, a box of tacks, and a book of matches:

Most individuals try to attach the candle to the wall using the tacks, which fails to meet the challenge and creates a waxy mess. Others try to use the matches to melt the side of the candle so it sticks to the wall, which never works.

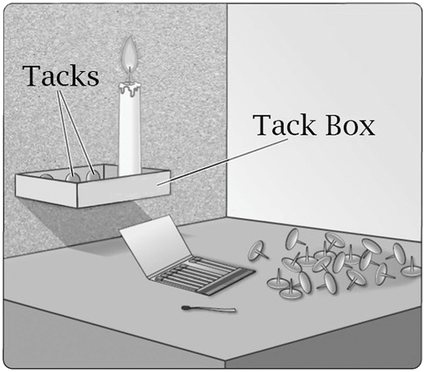

After making a mess, a burnt finger or three, and several failed approaches, someone figures it out:

The solution was there all along: the box. Using the tacks to pin the box to the wall creates a platform that can hold the candle and collect the wax, satisfying the challenge.

The box-candle problem is not only a test of creativity but also an example of functional fixedness: our tendency to see objects as functioning only in their usual or customary way.

I see the problem as something bigger: a reminder that in each of our lives, we have resources—skills, tools, assets—that we aren’t using to their fullest extent. Reminding ourselves of our under-utilized resources helps us reimagine the future.

My version of the box

Over a decade ago, an annoying chronic pain situation derailed my life. Due to a tendinitis-like soft tissue problem, using my hands—from typing to guitar to sports—became painful. I was sad about having to give up my hobbies of playing in bands and pickup basketball. But I was terrified about not being able to use a computer. I was a hard-charging tech entrepreneur. Would I be able to make a living? Have a career?

I became an expert in ergonomics and speech recognition software. Those solutions were helpful, but still lacking. The software never got my name right (No human has ever been named “Tam”) and I remember wanting to punch my computer (an act which someone with hand problems should not be doing). Necessity being the mother of invention, I started experimenting with using videos as a way to communicate with my team and customers. Despite how awkward it felt, sitting down and talking to the camera was the one thing I could do without pain.

Over the years, my skills with ergonomics, speech recognition, and video evolved to where I could use a computer well enough to at least not be worried about my ability to make a living. The companies I had started had done well enough that the University of Texas, my alma mater in Austin, asked me to teach a class on entrepreneurship. I was always curious about professor life, so I said yes.

Teaching was a joy but the money and bureaucracy were terrible. That’s when I got the itch to create my own online course where I could focus on maximizing what my students got out of it rather than keeping administrators happy.

Would I teach tech entrepreneurship? Business fundamentals? Digital marketing? Those all felt kind of vanilla. Anybody could teach those topics. I marinated on this question of how I could stand out for months.

But then I had my just-use-box moment.

Video was the skill I had that others perceived as valuable. I had learned hundreds of tricks for not sounding stiff and avoiding the awkwardness that comes after hitting record. I knew enough about microphones, lighting, and backgrounds to distill it into something simple.

That is how my course Minimum Viable Video was born.

What about you?

Whatever challenge you have in your life, ask yourself:

What skill do you have that you might not be using? Something that helps you stand out, that might be repurposed for something else? What is the box of tacks that you are not fully utilizing in your own life?

Rather than reading a book or doing more research, maybe you should just use what’s already at your disposal. And like that candle in the box, maybe it will shed some light on your situation.

Get weekly tips on entrepreneurship, video, and shooting your shot in my newsletter: https://www.camhouser.com/newsletter

Thanks to early readers: Jonny Bates